In 2007, the [U.S.] Brewers Association (BA) revoked the 'craft' brewery identification of Widmer Brothers. Widmer, the association decreed could no longer be pals with other 'craft' breweries, its birthright denied —despite it being one of 'craft' beer's pioneers, founded in 1984. Its crime? Anheuser-Busch had purchased thirty-two percent of Widmer's new tripartite partnership, the Craft Brew Alliance.

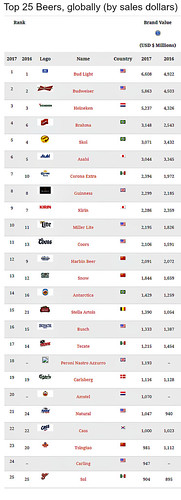

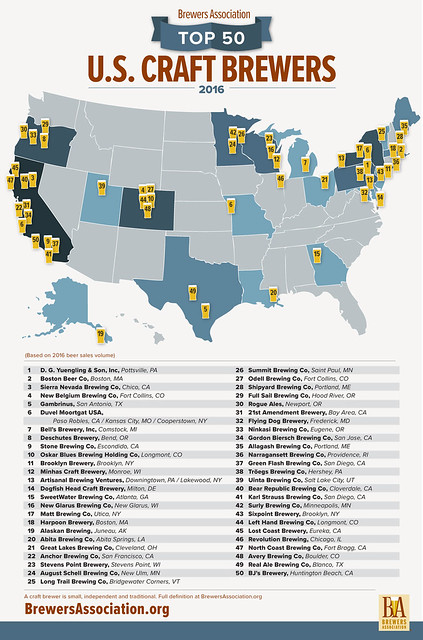

Fast forward ten years later. In March 2017, the BA released its list of the top 50 brewing companies in the U.S, ranked according to sales volumes. Look closely at this list. Forty of the fifty are 'craft' breweries, as defined by the BA.

Notice all those special notes, labeled "a" through "w"?

(I've listed them, and their multi-brewery exceptions, after the jump. Concurrently the BA compiled a list of the top 50 'craft' breweries —as it defines them— in the U.S. See that below the jump as well.)

In recent years, the

BA has been removing additional breweries, once considered fellow 'craft' brewery members, fast and furious from the membership roll. Beer writer

Jay Brooks succinctly found the absurdity in that:

Breweries in bold are considered to be “small and independent craft brewers” under the the BA’s current definition. That there are so many footnotes (23 in total, or almost half of the list) explaining exceptions or reasons for the specific entry, seems illustrative of a growing problem with the definition of what is a craft brewery. I certainly understand the need for a trade group to have a clearly defined set of criteria for membership, but I think the current one is getting increasingly outdated again, and it’s only been a few years since it was hotly debated by the BA. But it may be time to revisit that again.

Before revisiting, first this:

****************

An American history of brewing cooperation

In 1862, to fund their prosecution of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and the U.S. Congress adopted a one-dollar per barrel excise tax on beer. The following year, brewers of the Union (principally the lager brewers) joined forces to successfully lobby for a reduction: the levy was reduced to sixty cents. Although Congress would reinstate the higher tax, the group saw value in common cause and formalized its existence as the

United States Brewers Association. The organization would grow in size as the industry grew, only interrupted by Prohibition.

In 1942, small American breweries —"

pinned down by [WWII]

rationing and ambitious national shippers [large breweries]

on one side and a fusillade of federal regulations on the other"— felt slighted by the USBA and created a lobbying group for their own interests. They called it the

Small Brewers Committee, soon thereafter changing the name to the

Brewers Association of America. In 1976, the

USBA and

BAA jointly secured a tax differential on the first 60,000 barrels produced by 'small' breweries,' those producing fewer than two million barrels per year, maybe the high point of their political influence. That tax break still exists today.

By 1983, the

BAA was fast losing its members to closures and buy-outs (and itself to despair). An aspiring brewer named Mark Stutrud

wrote the organization asking for advice. It responded:

My dear Mr. Stutrud:

Thank you for your letter, and I note that you are working on a feasibility study on establishing a Micro-Brewery in the Twin Cities area. Please know that I am not encouraging you to do so, because it is a long and hard road that you planning to go down.

(Stutrud would ignore the 'advice.' He opened his brewery, Summit Brewing, in 1986, in St. Paul, Minnesota. It is still in operation, now the 27th-largest 'craft' brewery in the United States, producing 129,000 barrels of beer.)

Seeking a more potent advocate for nascent very small "microbreweries", Charlie Papazian founded the

Association of Brewers that year.

Three years later, in 1986, after 124 years of advocacy for American breweries, the

USBA was disbanded. Attrition had shrunk it to a mere forty-four brewing company-members, losing it the support of the largest American-owned mega-breweries, which replaced it with a new organization given the anodyne name, the

Beer Institute. Still operating today, the Beer Institute's putative mission is to represent all American breweries. In practice, however, it thrives as a lobbying representative of the large international brewing conglomerates —and associated businesses— operating in the United States. (It also serves a valuable historical purpose as a repository for American brewing records dating back to the Civil War.)

In 2005, the

Association of Brewers merged with the

Brewers Association of America —in reality, the former absorbing of the latter— forming the

Brewers Association. The new organization kept the

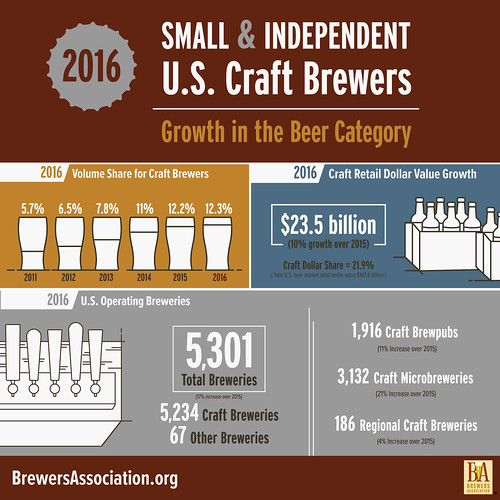

BAA's 1940s definition of 'small' brewery as one producing fewer than two million barrels per year (although adopting the term, 'craft' brewery.) In 2011, in danger of losing

Boston Beer Company and its dues and clout (the brewery was approaching the limit), the

Brewers Association moved the goalpost,

expanding the definition of "small" and "craft" from two to six million barrels.

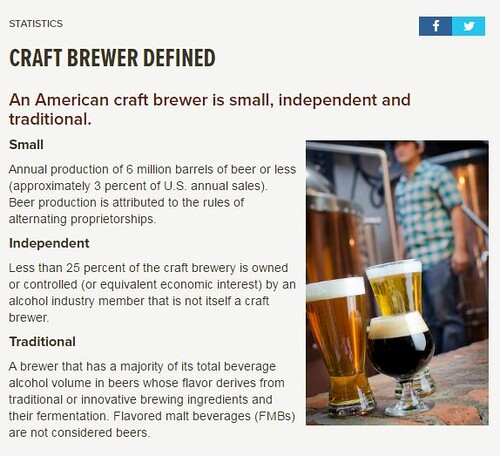

As it is defined now...

***************

Does 'craft' have meaning?

The

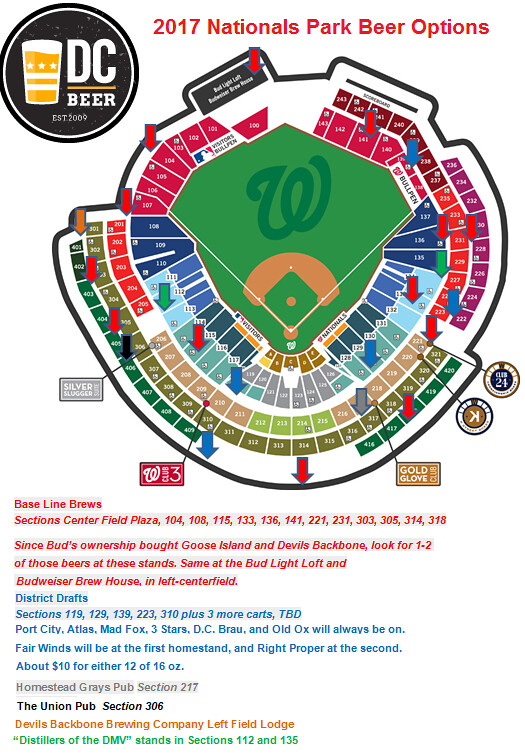

Craft Brewers Conference is the annual confabulation of the minds and mugs of America's 'craft' brewers. Next week, it returns to Washington, D.C.

The first time it had convened there, in 2013, its founder, Charlie Papazian

addressed the convocation without

ONCE using the term 'craft' brewery. He pointedly and repeatedly used the phrase "small and independent" breweries, even avoiding mention of the association's third stipulation for a 'craft' brewery: "traditional."

The [U.S.]

Brewers Association also takes no stand on what a 'craft' beer, per se, is or isn't. But prior to 2014, it did: forbidding the use of corn —a traditional American brewing ingredient— by any of its members in their flagship beers. In 2014, it altered that definition to graciously permit that starch.

Another stipulation goes to outside ownership. The

BA draws a red line for its 'craft' members at twenty-five percent ownership by any brewery that it does not consider 'craft.' Why that amount? Why not more (pristine) or why not less (restrictive)? What is so magical about less than a quarter?

The

BA remains silent when outside ownership belongs to a non-brewing entity. If, say, a hedge fund had invested in

Widmer rather than

Anheuser-Busch,

Widmer would still be a member in good standing in the

BA's 'craft' club. Why would it be less 'craft' to be owned by a brewery than to be owned by a venture capitalist, owing no allegiance to beer other than investment? A distinction seemingly without merit.

When the

BA increased the brewing limit of membership

two hundred percent from two to six million barrels per year, it de facto acknowledged the capriciousness of that limit. How did the marginal production of one barrel more than two-million justify the elimination of the 'craft' label? It didn't, and the

BA recalibrated. Now, how does "one toke over the (six-million barrel) line" eliminate 'craft'? Again, it doesn't. In defense of the ineffable, the

BA punishes the achievable.

And, so...

***************

A Modest Proposal

In anticipation of the upcoming national brewers conference, I suggest this

Modest Proposal.

The Brewers Association should dissolve itself

and reconstitute as the

United States Brewers Association.

Yes! The new

United States Brewers Association (USBA) could be, as it once was, the advocate of

all American breweries: the very large, the regional, the small, the very small, production-only or brewpub, local or national. What the

USBA would

not be is the representative of foreign-owned breweries. To be a member, a brewery would have to be, at a minimum, fifty percent American-owned. That, like a majority vote, seems less arbitrary than the current twenty-five percent 'craft' limit. No convoluted pretzel-twisting definitions and no time-wasting semantics. No thanks, Anheuser-Busch InBev!

*

All

American breweries —from the family-owned three-million-plus barrel-per-year Yuengling Brewery to the nano-est 100-barrels-per-year

nano-brewery— could find common ground to work together, barrel-by-barrel, toward their common interests. Whether corn —or cocoa-puffs or dingleberries— could constitute the grist of a 'craft' beer would be a moot question relegated to

Reddit and blogs like this one.

Problems? Of course. The simmering conflict between large and small 'craft' would continue and the differing concerns of production breweries and brewpubs would continue, even

as they do now. But after the change, those interests, common and separate, would be addressed as between

American breweries. The smug moral superiority of a nebulous 'craft' imprimatur would be rent. Come back

Widmer! Come back

Founders; come back

Lagunitas; come back all of you. Forgive us!

Back to the future:

***************

The United States Brewers Association

A resurrected

USBA could end the jumble of fungible

barrelage requirements, ingredient

self-righteousness, and convoluted arguments about what exactly a

'craft' brewery is or isn't. Any opinions between outside brewery ownership or venture capital ownership would be rendered moot...at a fifty percent stake or less, that is.

This is a solution that acknowledges reality. It avoids subjectivity. It pays homage to American brewing history. It does not penalize success. It increases the industry's economic and political clout. (And, gasp, it's patriotic.)

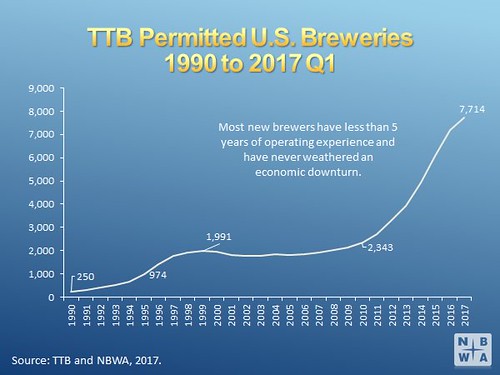

In 1978, there were 44 breweries in the United States. As of the end of March 2017, there were

7,714 operating brewery licenses. Thank you, [U.S.]

Brewers Association.

Now, live long,

United States Brewers Association, and prosper.

-----more-----